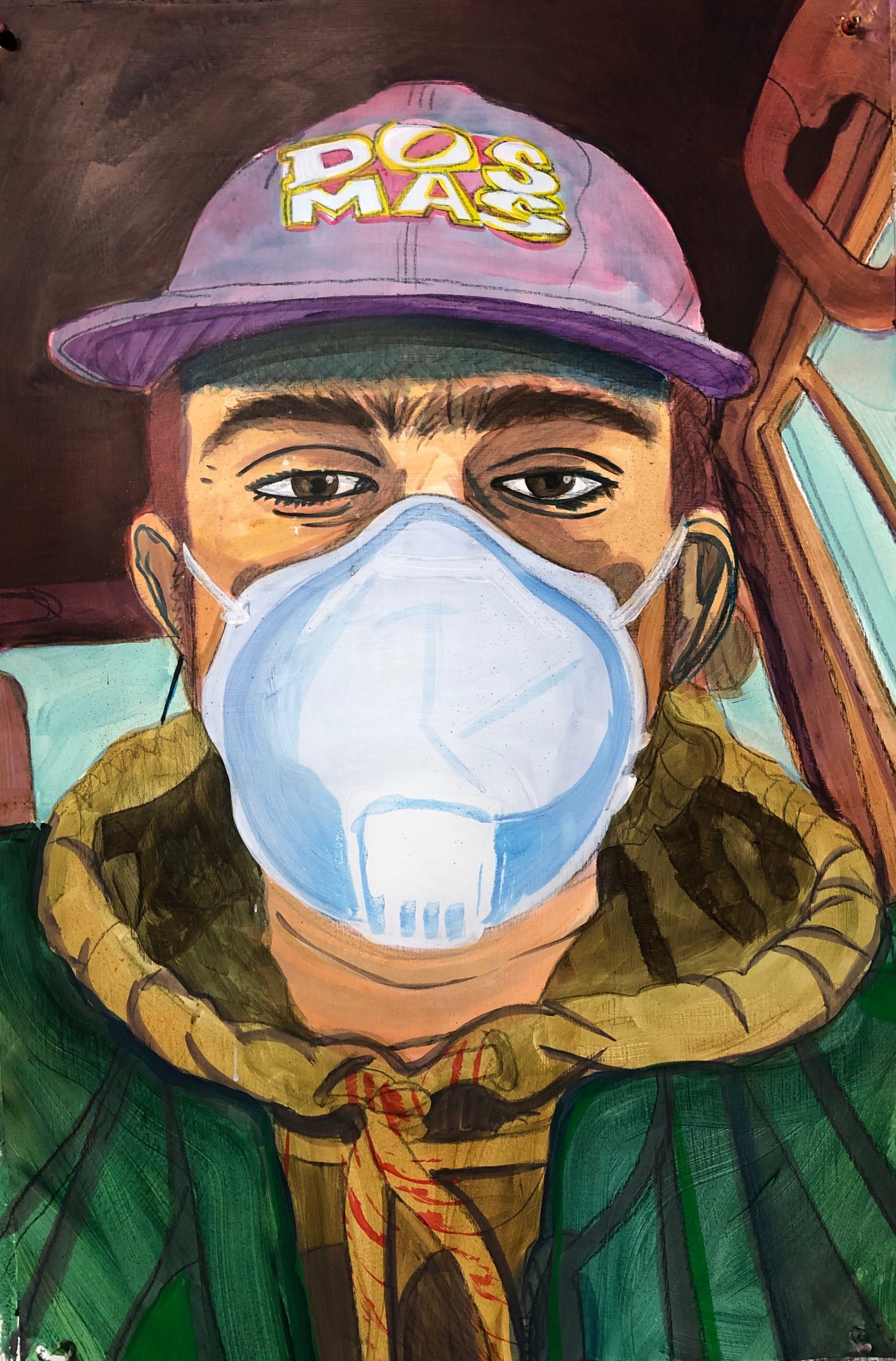

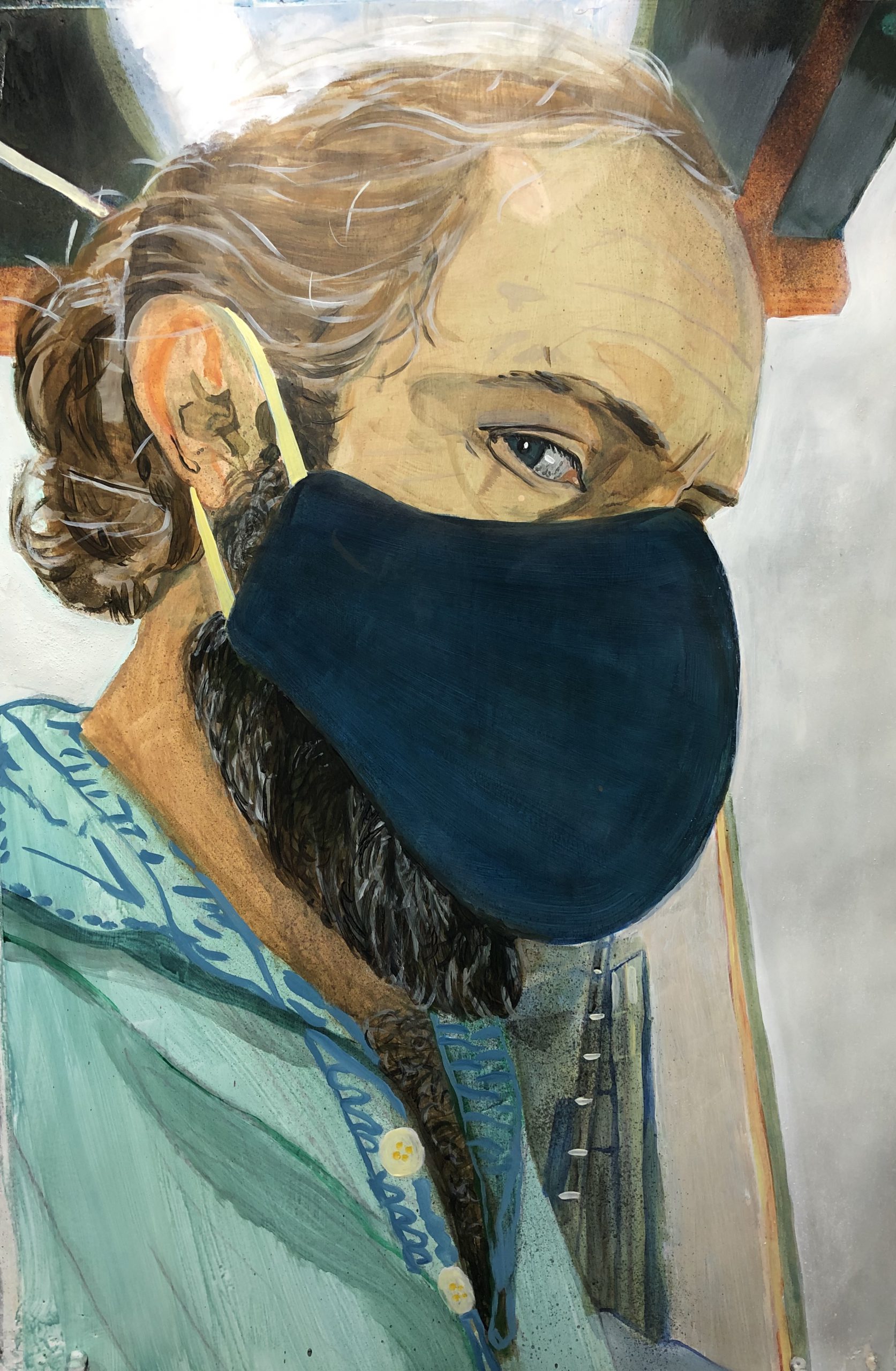

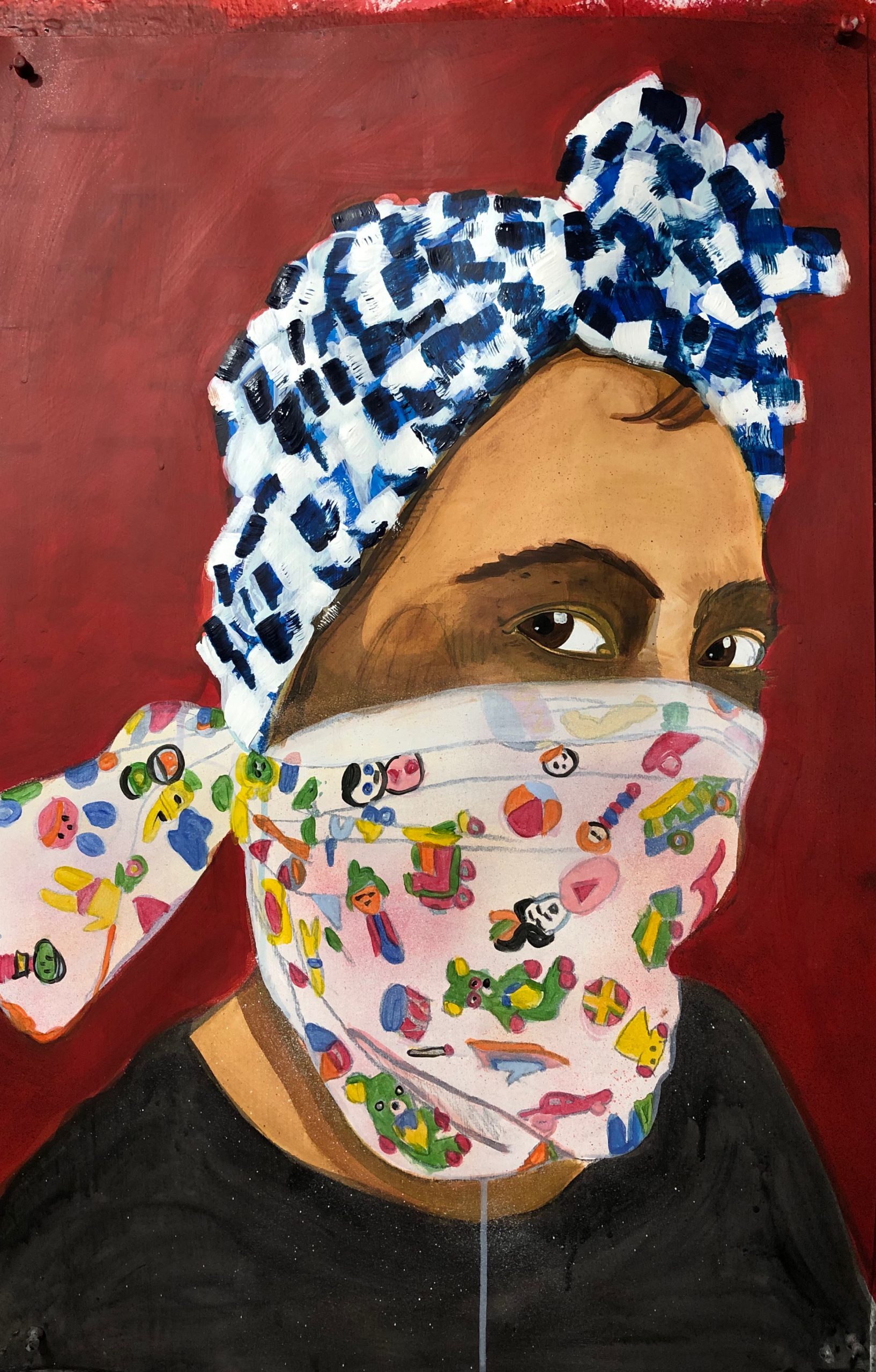

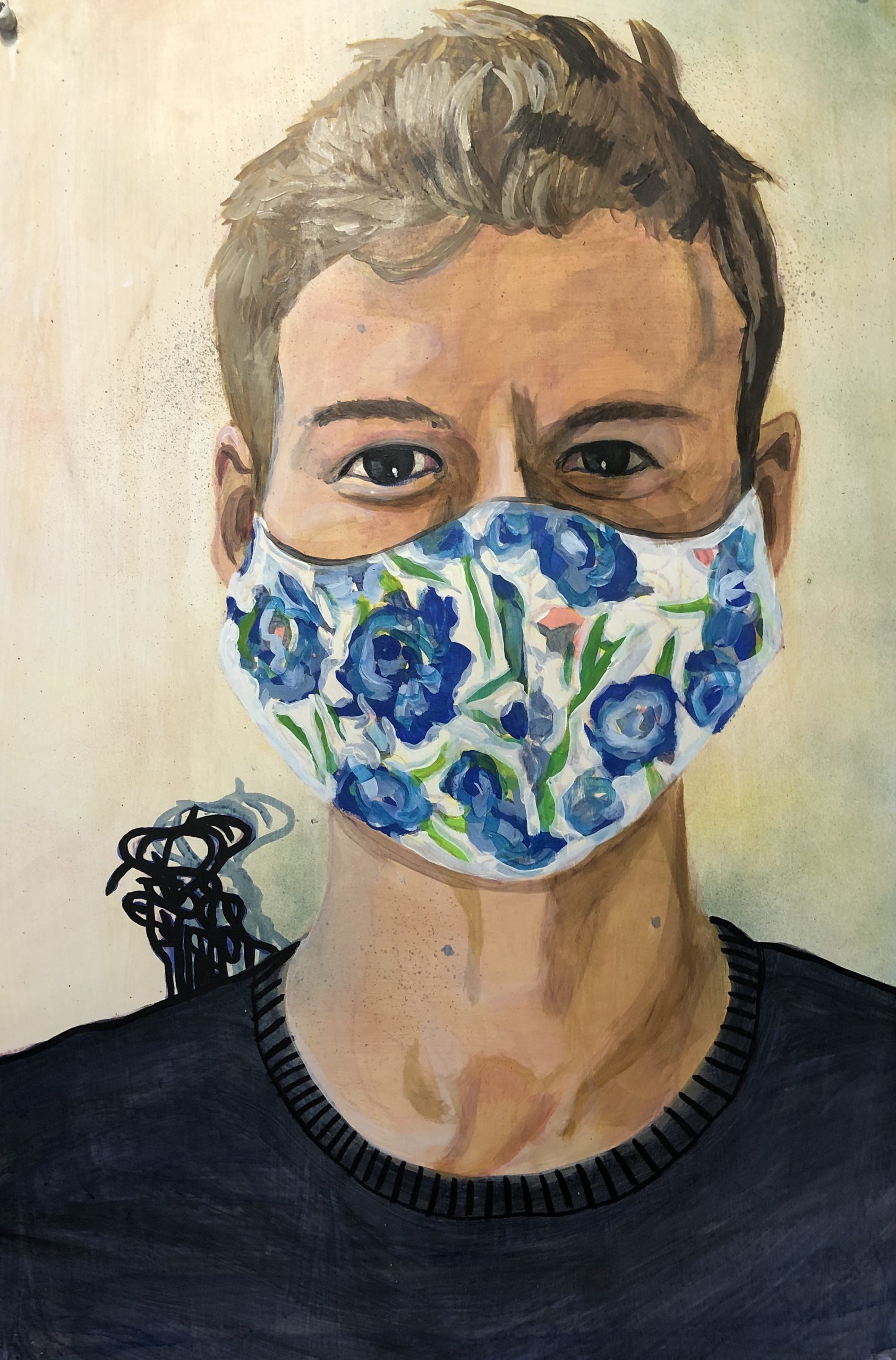

Covid portraits

“Mankind will endure when the world appreciates the logic of diversity.”

—Indira Gandhi

Transitory Democracy: Recent Portraits by Richard Nielsen

In spite of our continual awareness of how the physiognomic analysis of an individual’s facial features are capable of revealing an inner life, spirit, soul, and personality, we continue to wonder how this function of photography has endlessly provided “knowledge dissociated from and independent of experience” as Susan Sontag wrote in her landmark book On Photography in 1977. While technical imagery continues to evolve through endless inventions and permutations, through meditations with time, artists—in particular painters—have a specific affinity towards the ways in which relationships with their immediate surroundings and social contexts often times can be perceived as conflicts with each other, be it fact versus fiction, the seen versus the unseen, and above all the minute distinction of difference vs. repetition. While at other times they’re beheld as concrete realizations of highly-made imagery. In other words, everything that belongs to photography offers countless visual prioritization of what matters most to each painter. Their ultimate challenge then lies in the strand of hair that separates what is regarded as a personal experience during the process of making and what could be rendered as a universal representation upon completion, upon completion at the expense of the painter's dualistic nature—a maker with the dexterity of hands and a viewer with the incision of sight, either at odds or in accord.

Each painter’s aspiration, in either case, is to construct a possible unity between the biological and the physiological in a human face through technical aptitude and the requisite of observation. Since John Szarkowski’s famous assertion “the world now contains more photographs than bricks, and they are, astonishingly, all different,” we have come to realize the power of photographs; the mere virtue of their reproductive multiplicity is their colossal capacity to level everything they depict. This has been heightened from the mid to late 2000s when Facebook (and its subsequent technologies such as Twitter, Instagram, and so on) brought about selfies, hashtags, and began to aggressively influence our mainstream media—our ever spoon-fed Society of the Spectacle. None of us anticipated the unprecedented and relentless assault of this technology on our private and public spaces alike, as it has since the 2016 presidential election of Donald J. Trump, as well as the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic (since March 2020).

In the case of Richard Nielsen, an artist whose creative arsenal includes almost every medium in the visual arts, from painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking, and photography to environmental design and social activism (which instead of surrendering to the academic emphasis on specialization, a lifetime commitment to one field of discipline), Nielsen’s orbit of media can be called upon, activated, and deployed readily and accordingly. His collaboration with his partner Lauren Bon and her practice Metabolic Studio since 2007 has been indispensable to his affirmation as an artist with greater clarity and a broader worldview. The Optics Division, a photographic tool of Metabolic Studio, is a collaborative project within the studio that since 2010 has been a collaboration between artists Bon, Nielsen, and Tristan Duke.

Having recognized by mid-March the pandemic that led to physical distancing among us fellow human beings, as well as the interruption of our constant, unbroken rhythms of our urban lives, largely dictated by speed and technology, from which we were forced to significantly slow down, Nielsen expeditiously embraced the natural condition of “slowness” as an intrinsic and elemental requirement of our humanistic inquiry. Similar to how we each have our own personal power of insight in response to short- and long-term events, tragedies that are most often inflicted by man’s self-destructive impulses or on some occasions by natural disasters compel us to undertake immediate pathways for self-introspection, or whatever means that bestow extended variables for self-meditation.

Liminal Portrait “Ansel”, 2018

Optics Division, Metabolic Studio.

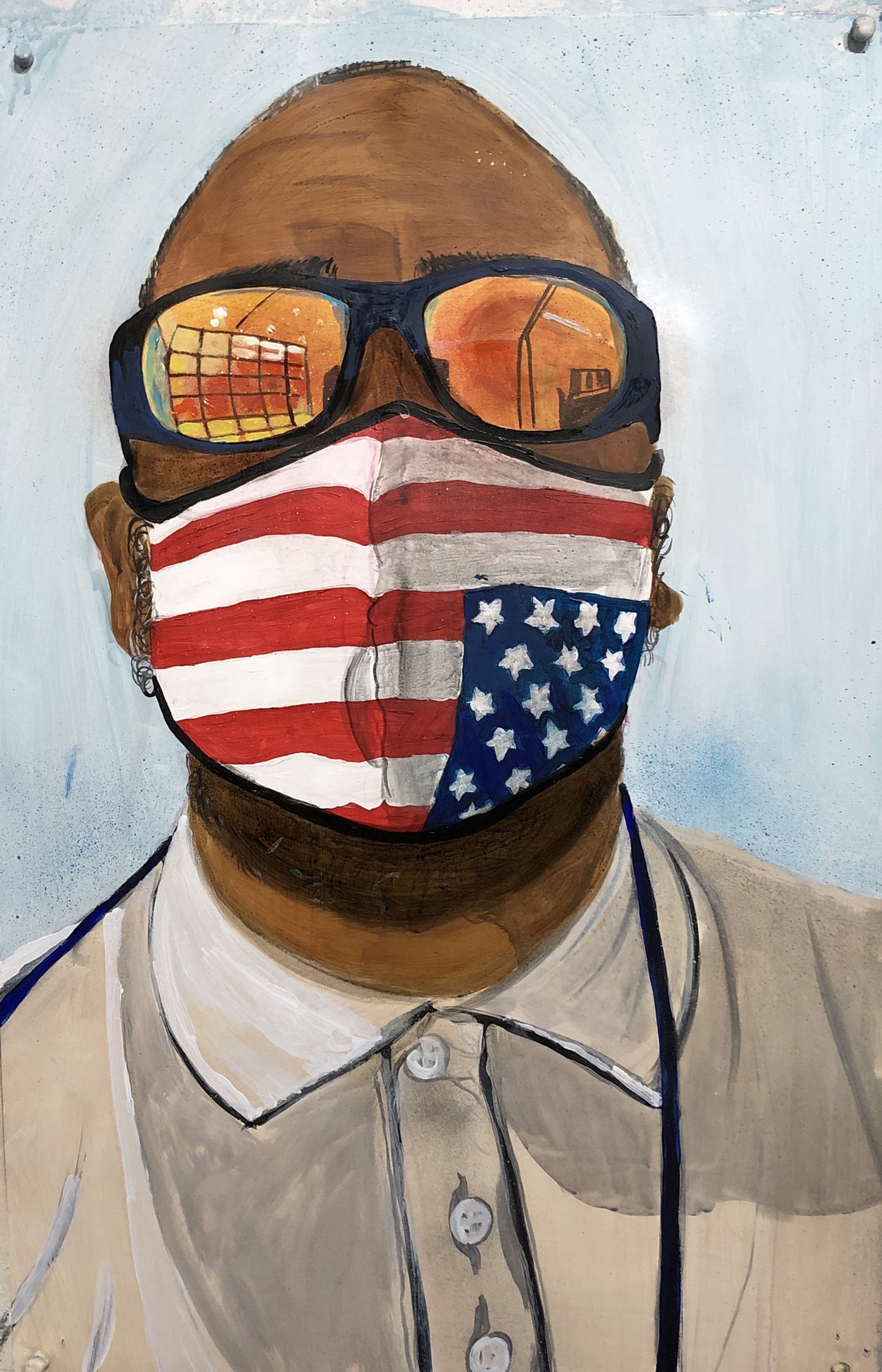

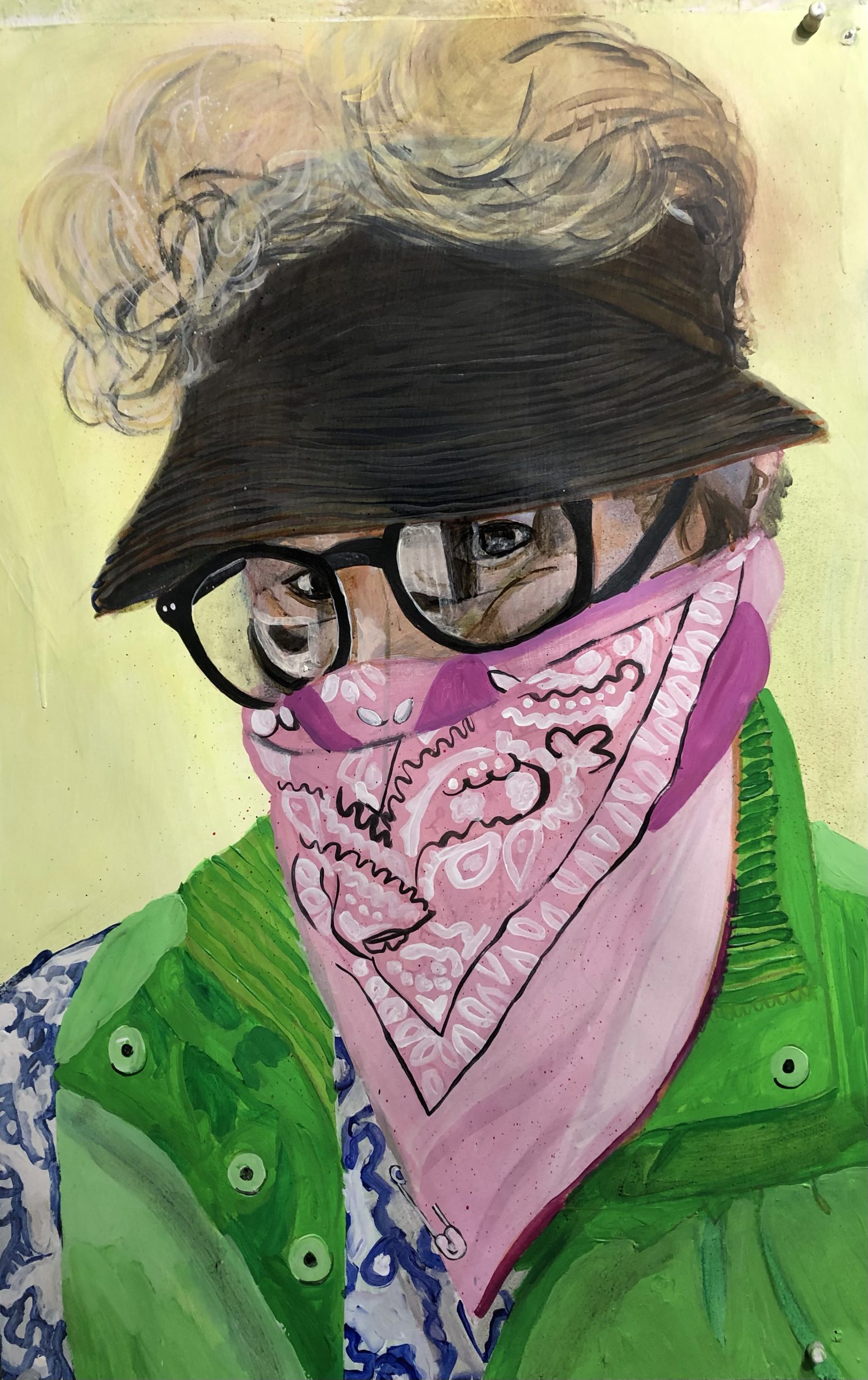

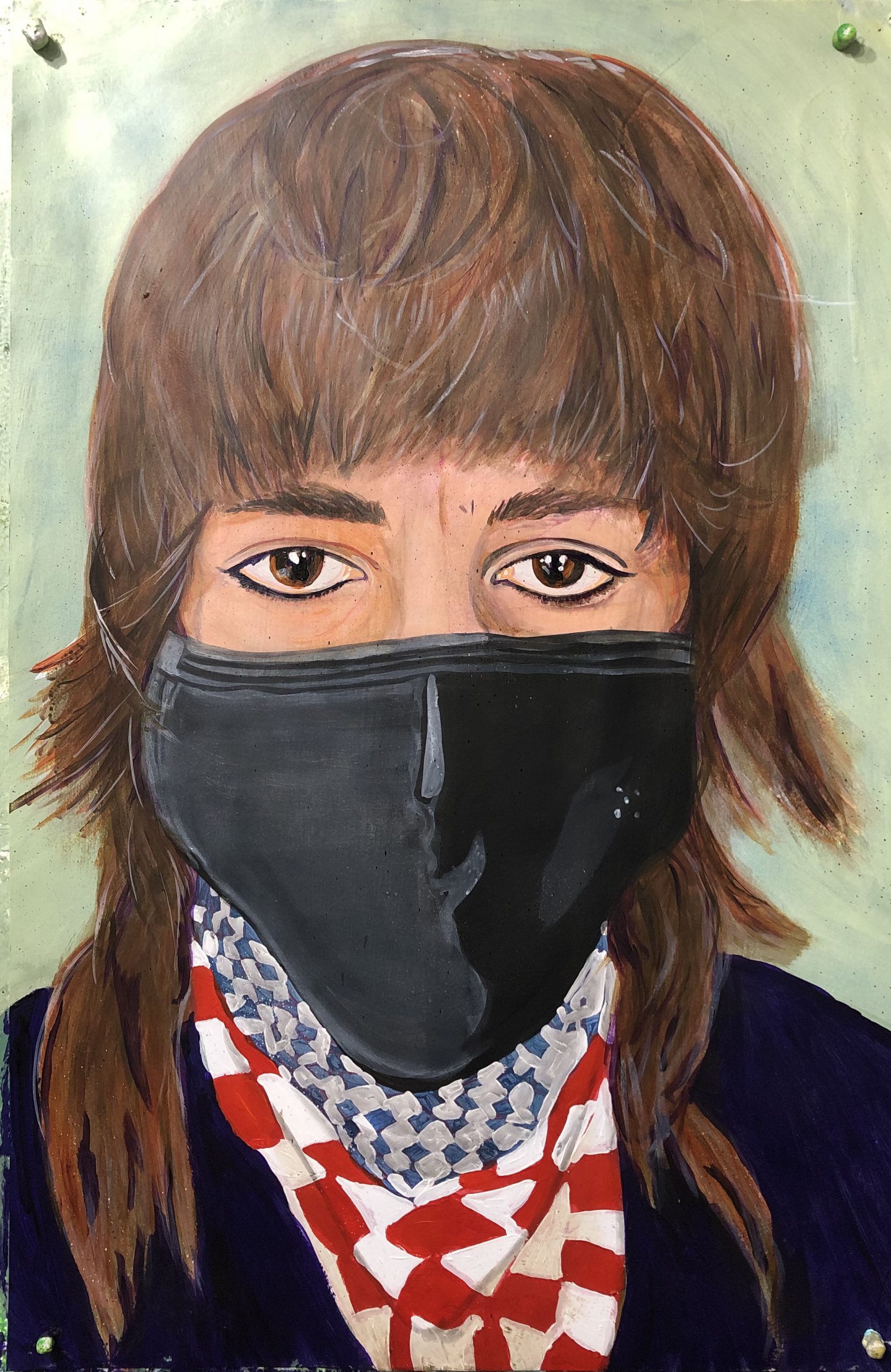

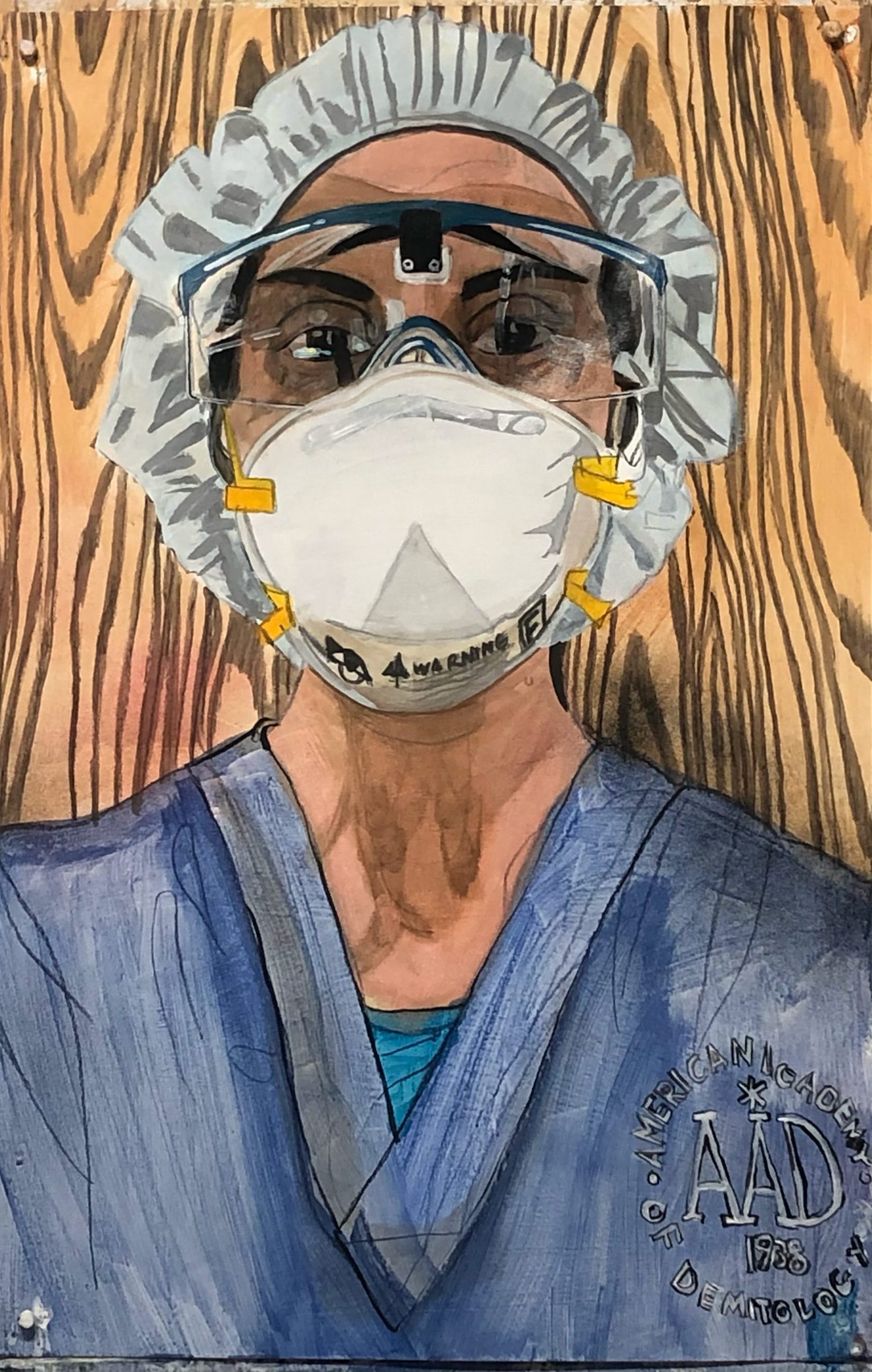

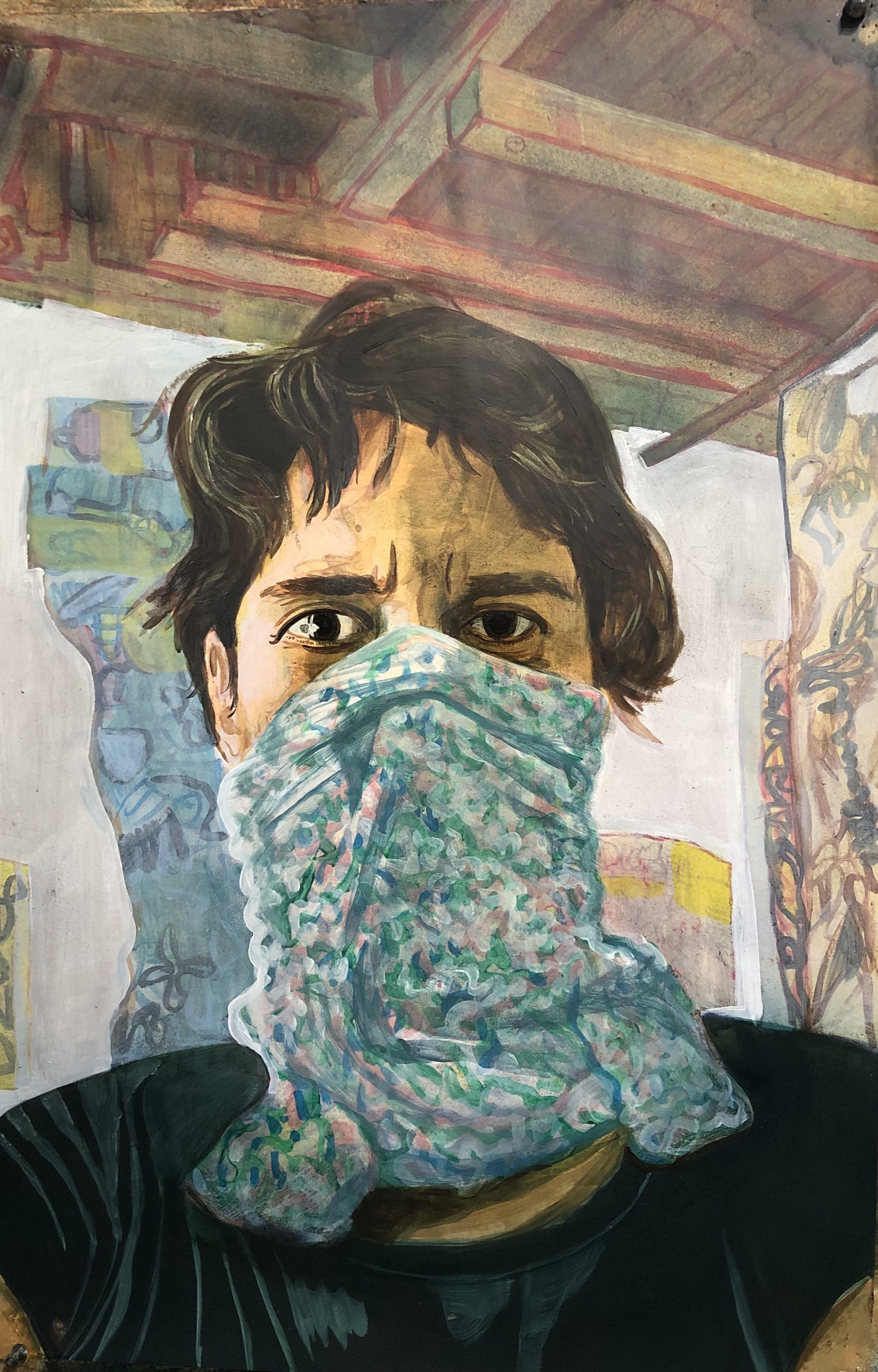

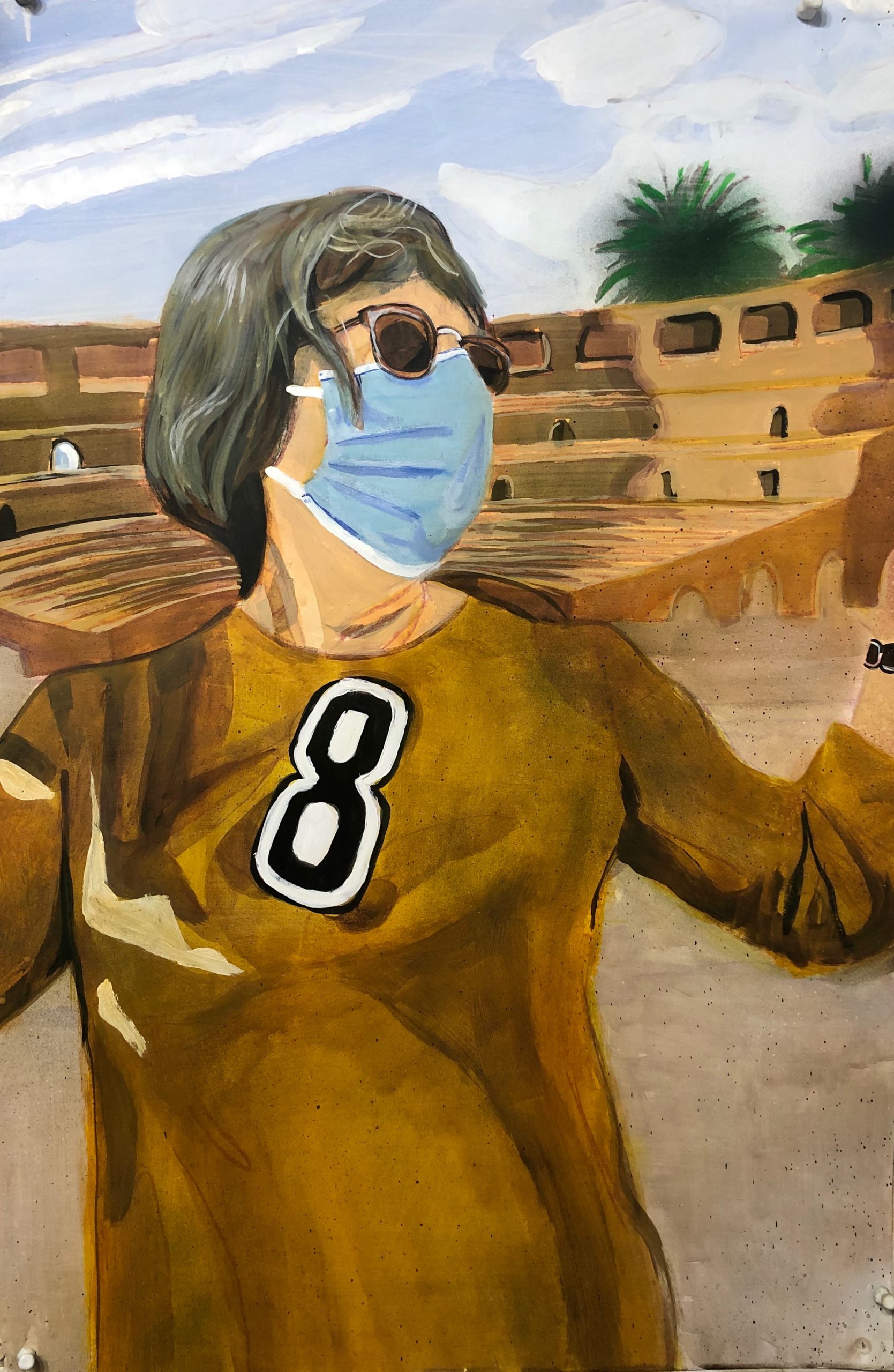

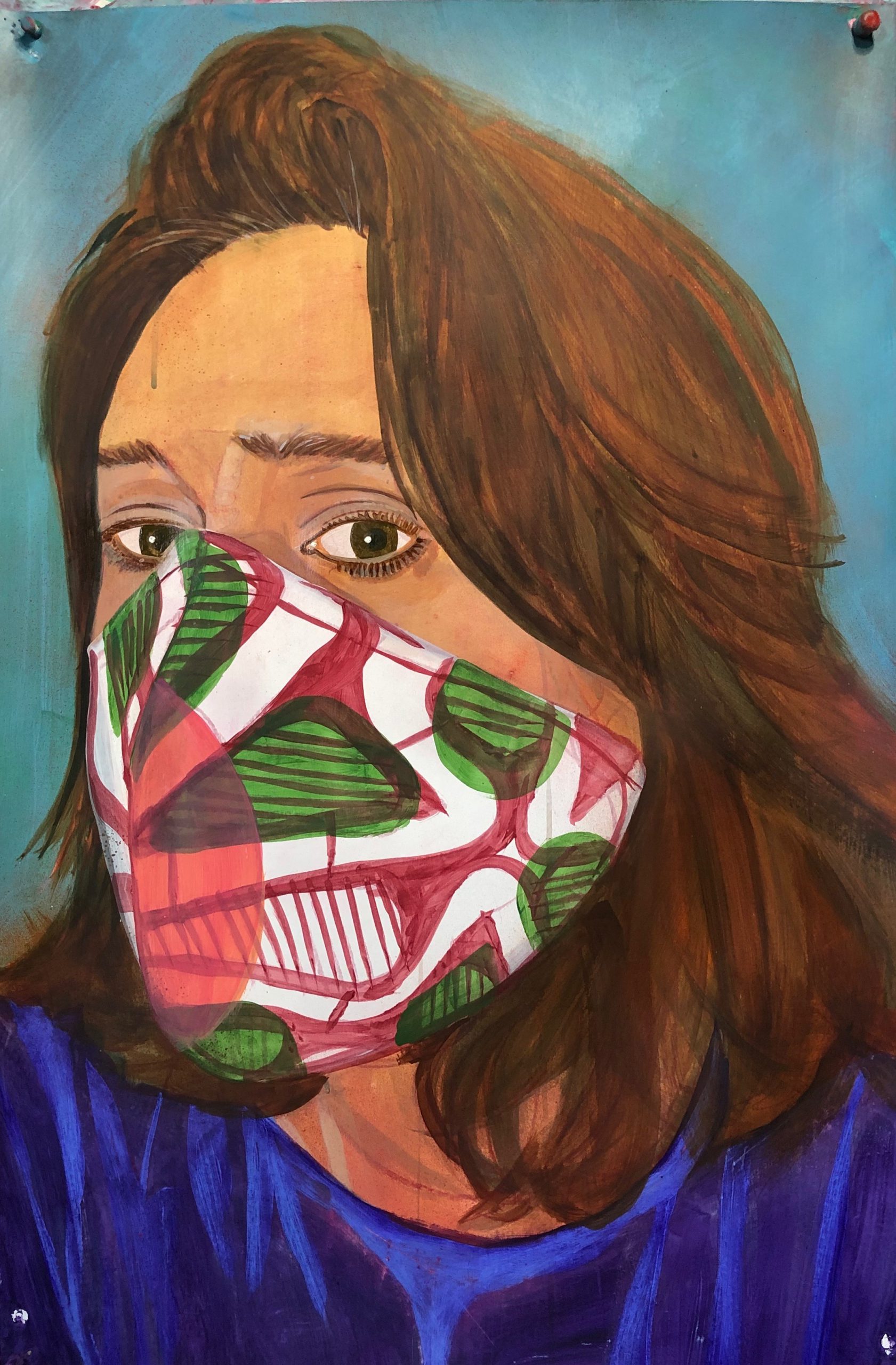

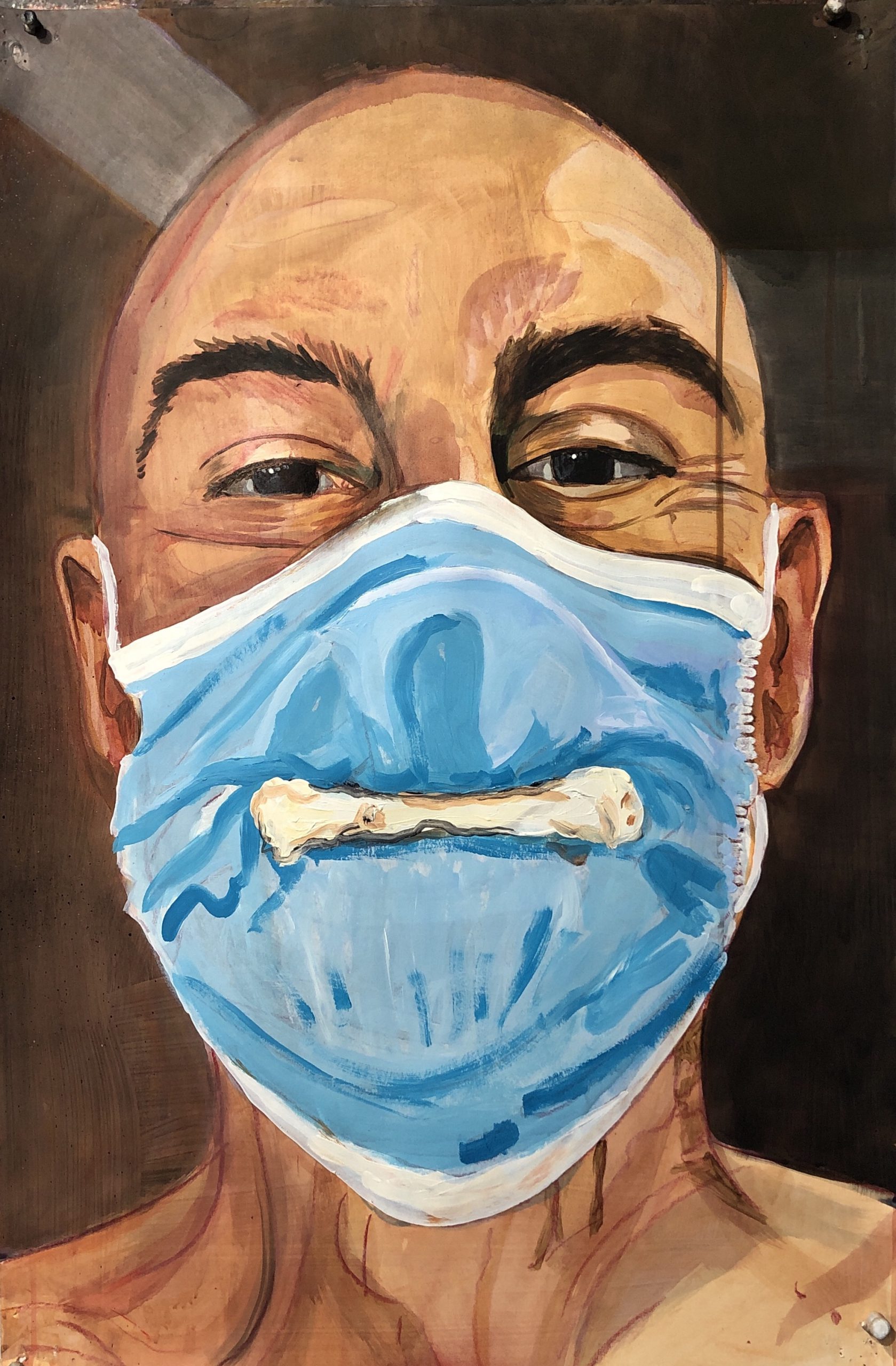

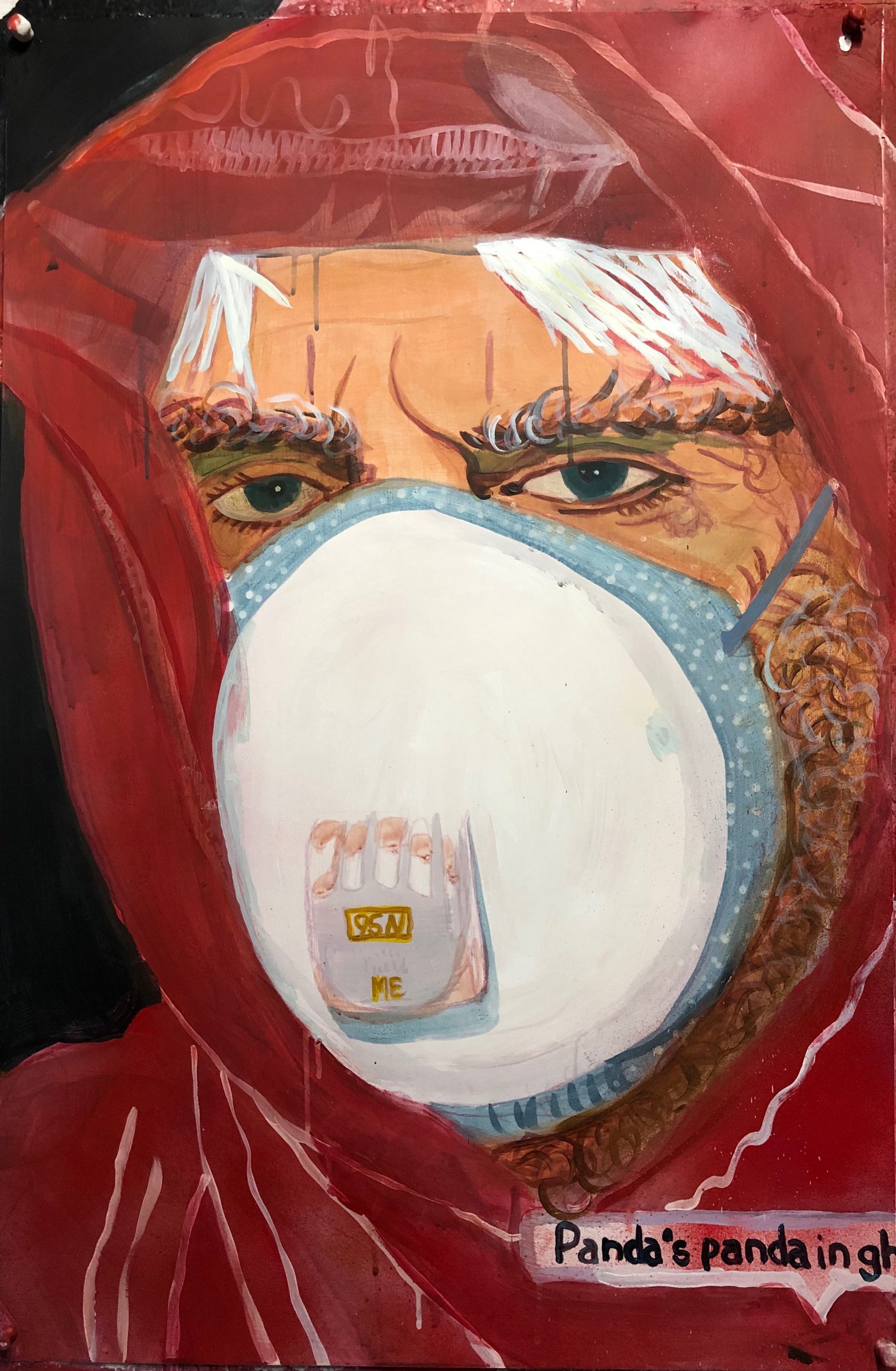

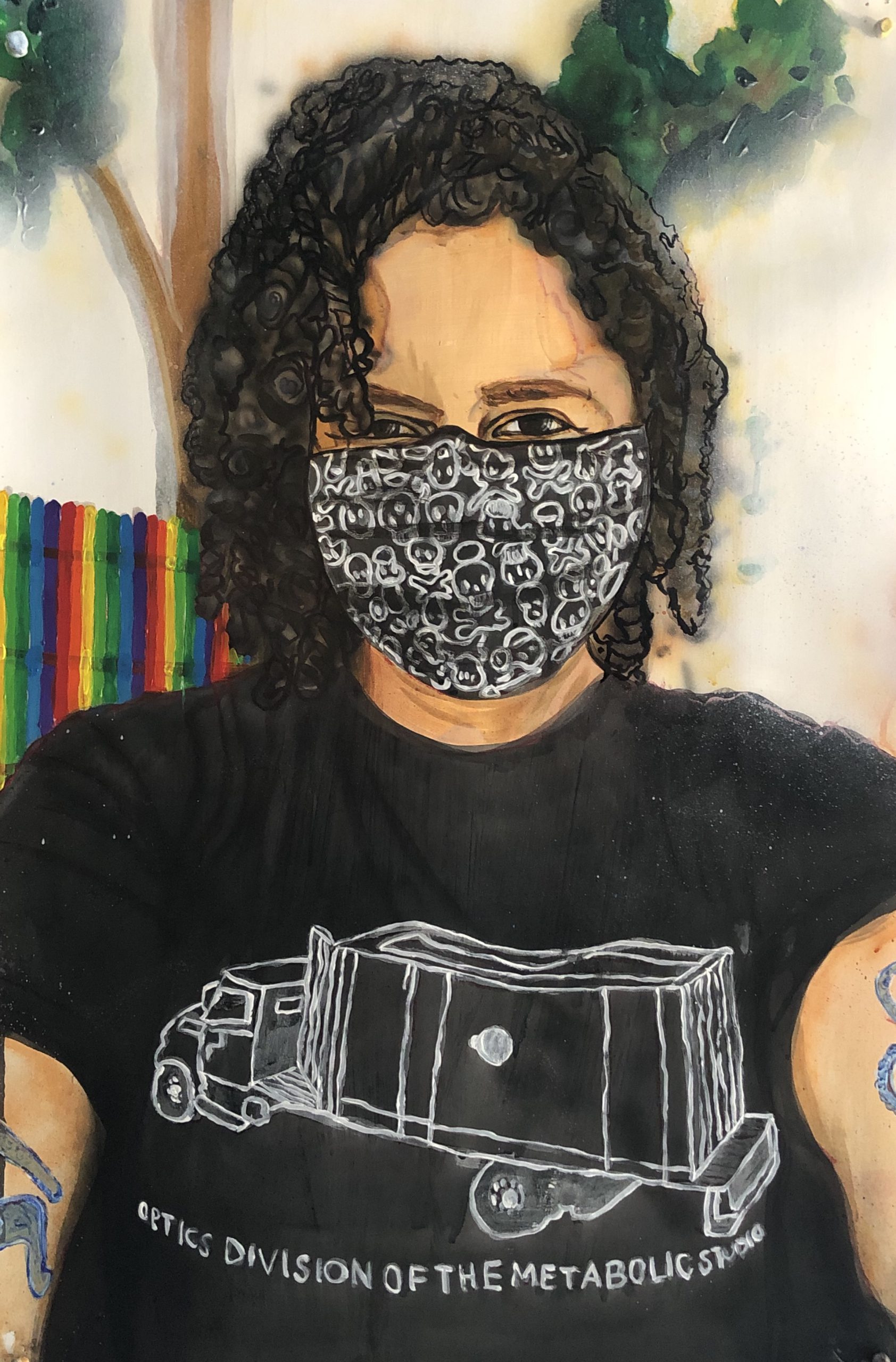

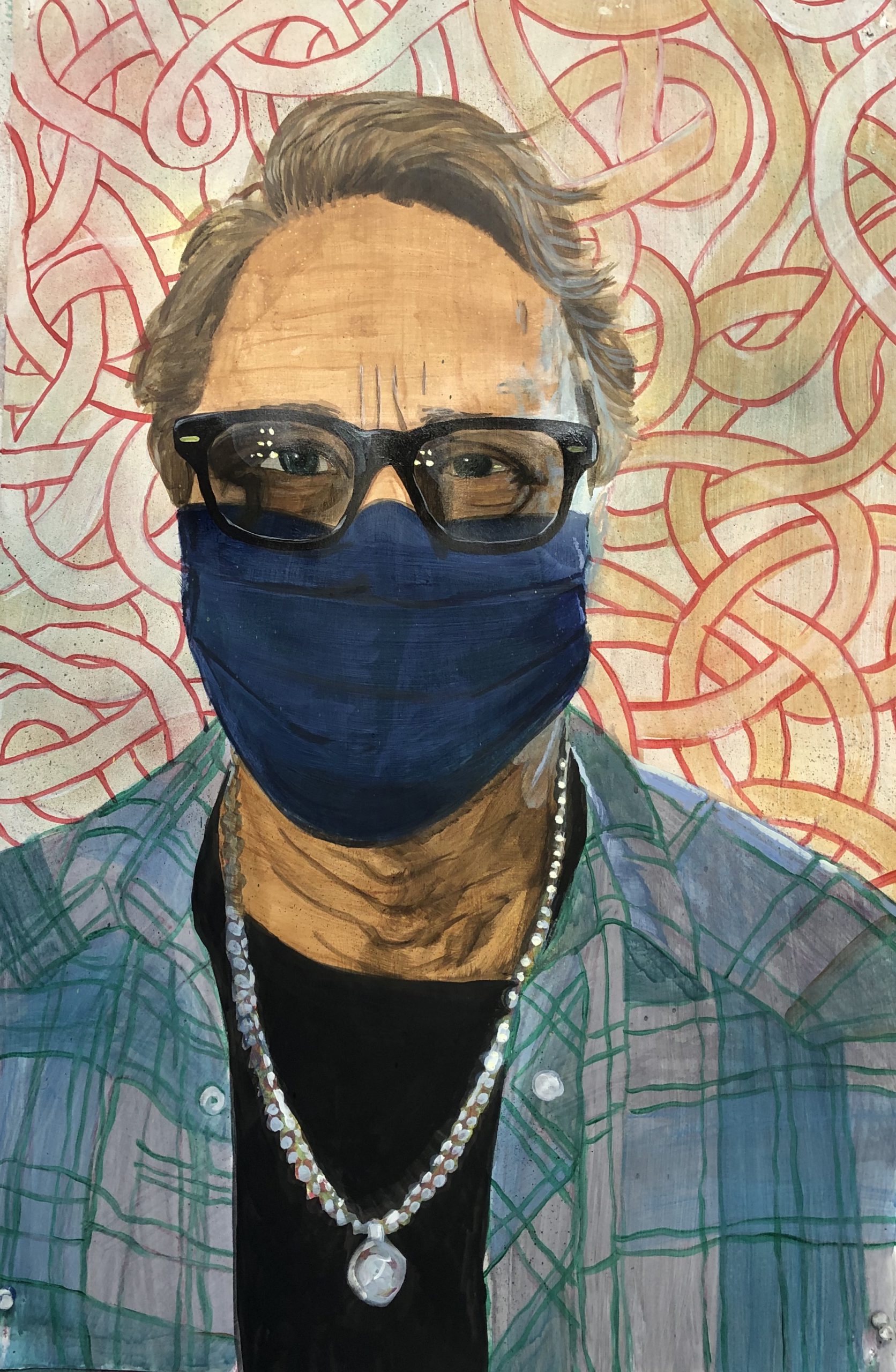

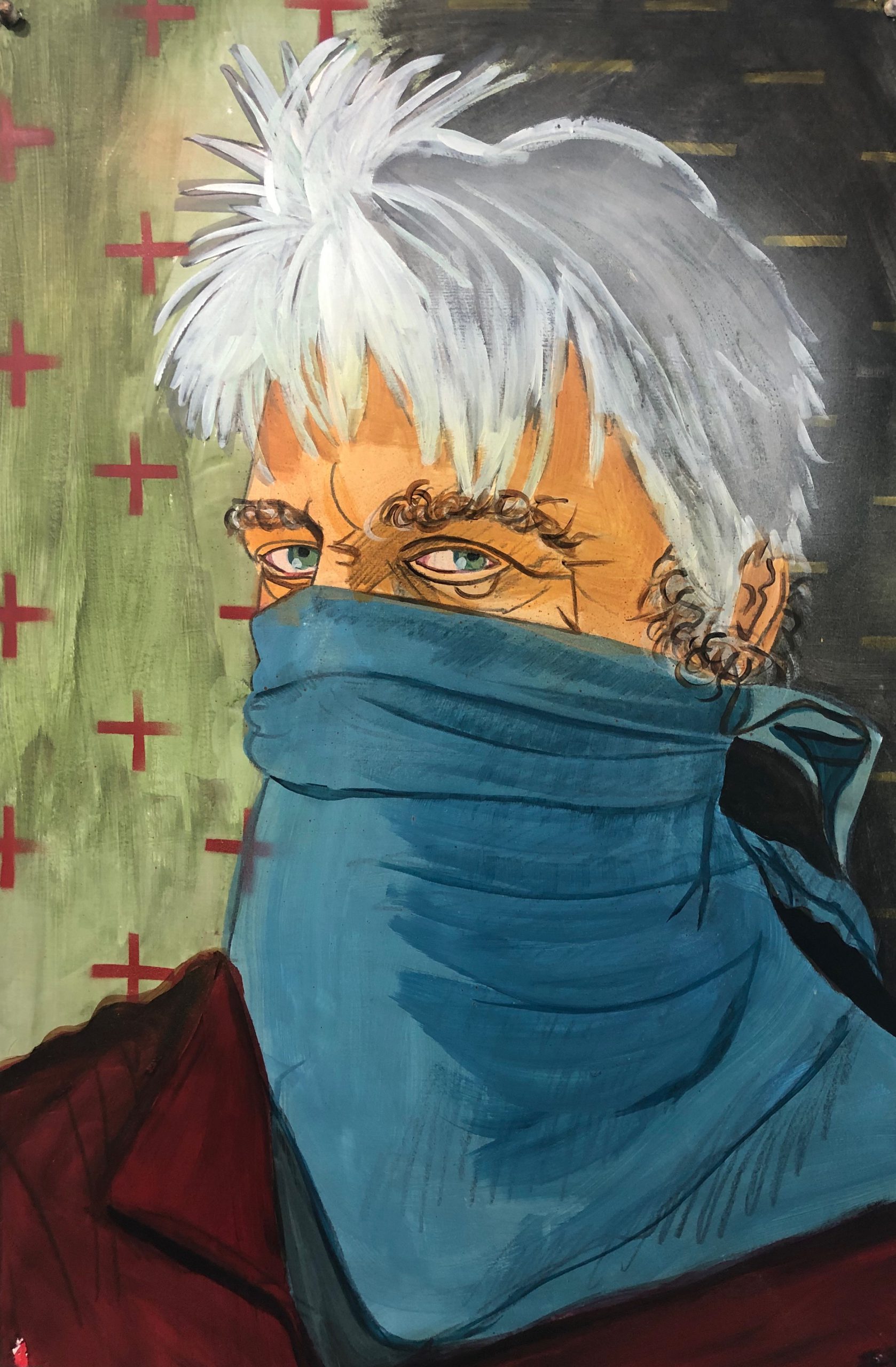

Again, from the outset when shelter-in-place orders and face masks to be worn in public were mandatory, Nielsen instantly entrusted painting as his medium of choice and the faces of his friends, family members, and colleagues wearing masks as his subjects. Since Covid-19 rapidly became a global pandemic by late March 2020, we’ve not only lost over 220,000 lives in the US and over 1 million worldwide to date, but our global economy is collapsing while social unrest spurred by divisive policy and systemic racial injustice is intensifying in every city on earth. The question remains, what and how are we to meditate, recognize before reconcile, and heal these inflictions that were essentially created by our own absent-mindedness and complicity? Many of us, if not all, are inspired to heal as a way to make real progress through the actual mediation of voices from all walks of life. Most of us have come to realize that every form of meditation requires thinking continuously about one object of thought before transforming into feeling. For meditation being a process that offers a potential migration from the complexity of the mind to the simplicity of the heart, it depends upon an act of repetition, which has different implications for different artists, in how he, she, or they apply it to their work.

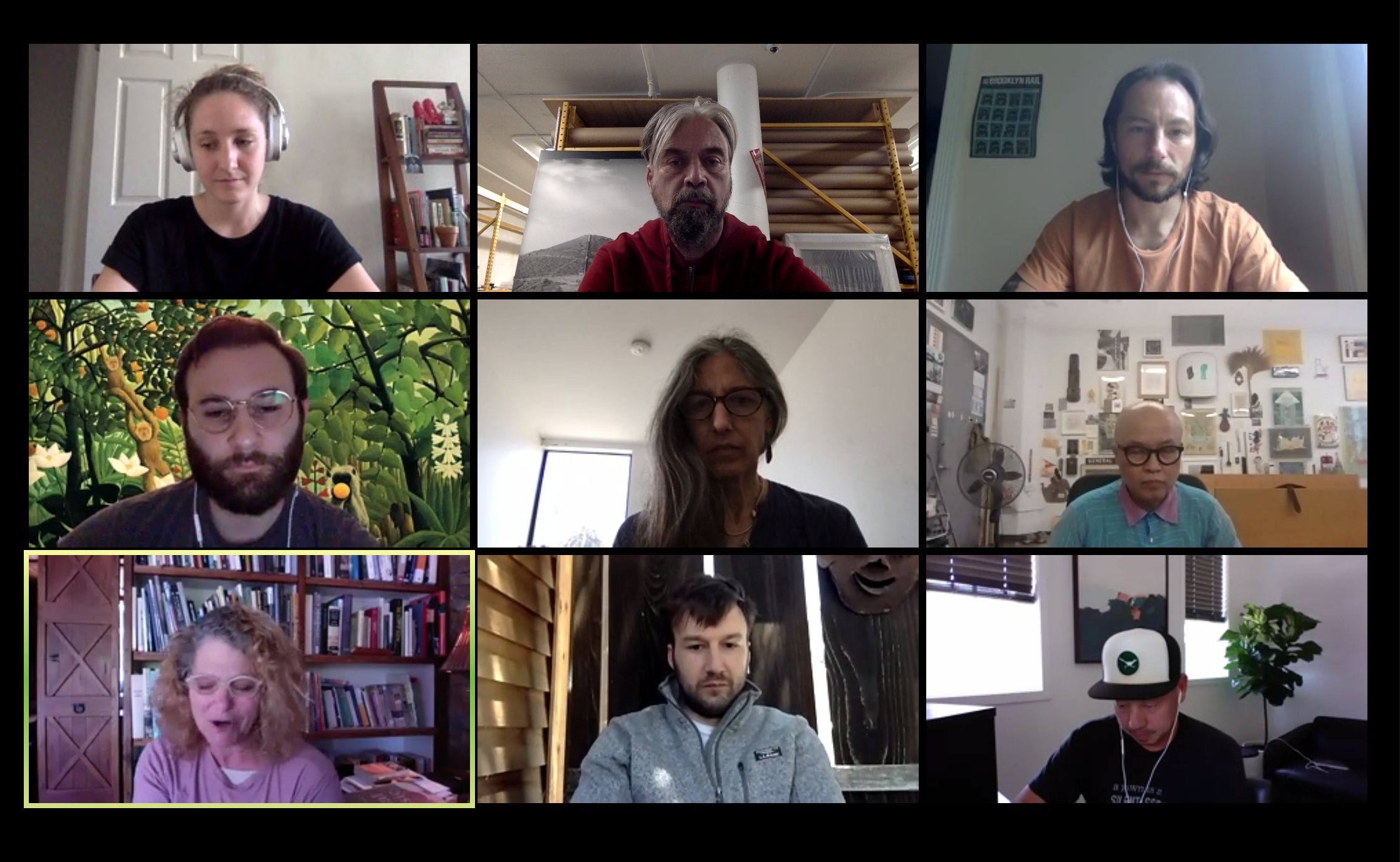

Brooklyn Rail / Metabolic Studio, Zoom meeting, 2020

In Nielsen’s case, by befittingly recognizing the grid structure—that also congregates in the Brooklyn Rail’s New Social Environment daily conversation series (launched a day after the Trump Administration’s announcement of the 15 day quarantine and social distancing in public on March 16, 2020) and Metabolic Studio’s Interdependence Salon (launched April 20, 2020), as examples par excellence that bring various and diverse communities together to amplify the much needed intimacy of sociability that distance has hindered—he immediately began in his first days of quarantine painting a series of 6 self-portraits wearing a respirator with materials he had at hand (acrylic paint on 23 1/2 x 36 inches, 120 pounds of Mayfair printmaking paper, which he gessoed on both sides, front and back for archival purposes). As an urgent need to activate his own meditation on the endless onslaught of the so-called “Breaking News” that dominates our daily lives with the latest updates of protests infused with countless scandals surrounding the Trump Administration, and most recently the 2020 election, Nielsen adapts his own grid structure that allows him to make portraits of people from his expansive community as an ongoing project, from which this group of 48 faces and one self-portrait were selected for this exhibition. He also recognizes how the grid structure from the Zoom platform humanizes those who appear in it, in spite of their diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Among them are, for example, Denise Markonish (curator at Mass MoCA); Joe Thompson (former director of Mass MoCA); Lauren Bon (Nielsen’s partner, artist, founder of Metabolic Studio), Tristian Duke (artist, co-founder of the Optics Division at Metabolic Studio) and in addition, there friends and colleagues from different communities across the country: those from LA for example, James Elaine (former curator at the Hammer Museum), William Basinski (composer, visual artist), Suzanne Lacy (art historian); along with Charles Schultz (the Brooklyn Rail's Managing Editor), Nick Bennett (the Rail’s Special Projects Editor), Shaun Leonardo (multidisciplinary artist) from New York, Nick Cave (sculptor, dancer, performing artist) from Chicago, Trenton Doyle Hancock (painter, sculptor, performance artist) from Houston, Ansel Krut (painter) from London.

Unlike Andy Warhol’s grids, where the minute imperfections separate them from the mass-produced products as seen in our supermarkets, Nielsen welcomes and astonishingly embraces chance operations, not knowing the content of the submitted selfies, rather only knowing that each would be painted within his pre-established 23 1/2 x 36 inch vertical format. This admittance of chance operations evokes an ideal of self-correcting democracy, for democracy itself was never meant to be a permanent condition of governing or a fixed social and political system. Nielsen, using this sensitive and compassionate perspective, grants life experience to enter art instead of art informing life. In addition to the differences in each portrait, be it scale, depth of field, angles, or notably the design variance in face masks that both obscure the face yet constitute the individual freedom of expression of each of the subjects, what we see in this particular ensemble is how Nielsen takes an ecstatic liberty to explore different backgrounds, so while on one hand he attenuates the faces of the sitters,each is treated with a distinct aura of their personality and spirit.

In the midst of what we’ve been experiencing during this historic pandemic together as a nation and as individuals, the fragility of our democracy has not been so amplified since the Civil War in the 1860s, the Great Depression in the 1930s, or the civil unrest of the late 1960s. Richard Nielsen’s transitory portraits offer a profound optimism and a reminder that instead of coercing our Americans into a “melting pot,” or the opposite, by dividing them as insular groups against one another, we should think of ourselves as instruments that each have a unique sound that when brought together can play harmoniously in the symphony of humanity.

Phong H. Bui

Publisher and artistic director, Brooklyn Rail

Brooklyn, October 2020